Dinamica dei nutrienti • Principali funzioni degli elementi nutritivi • Sintomi di carenza nutrizionale • Riferimenti analisi fogliari • Fabbisogni totali in elementi

1. Manuale di coltivazione del pomodoro: Dinamica dei nutrienti

Il picco dell'assorbimento del Potassio si ha durante lo sviluppo del frutto mentre l'assorbimento dell'Azoto si ha principalmente in seguito alla formazione dei frutti del primo palco (Figs. 5 and 6).

Il fabbisogno e l'assorbimento del Fosforo (P), del Calcio (Ca) e del Magnesio (Mg) è relativamente costante durante tutto il ciclo del pomodoro.

(Source: Huett, 1985)

Figura 5: Dinamica di assorbimento di Macro e Meso elementi da parte di una pianta di pomodoro

Assorbimento (g/pianta) |  |

Figura 6: Assorbimento giornaliero dei Macronutrienti da parte di un pomodoro da industria con una resa di 127 T/ha

(Source: B. Bar-Yosef . Fertilization under drip irrigation)

Assorbimento (kg/ha/day) |  |

Giorni dal trapianto |

Come si può evidenziare dalle Figure 5 e 6 la maggior parte dell'assorbimento dei nutrienti avviene tra l'8a e la 14a settimana di crescita, un altro picco di assorbimento (specifico per i pomodori da mensa) si ha in seguito al primo stacco. Pertanto la coltura necessita di un elevato apporto di azoto nelle fasi precoci della crescita con ulteriori applicazioni nelle fasi iniziali dello sviluppo del frutto.

Una maggior efficienza d'uso dell'azoto si raggiunge grazie alla fertirrigazione sotto pacciamatura o in sub irrigazione.

Almeno il 50% dell'apporto totale di Azoto dovrebbe essere sotto forma di Azoto nitrico (N-NO3-).

Una maggior efficienza d'uso dell'azoto si raggiunge grazie alla fertirrigazione sotto pacciamatura o in sub irrigazione.

Almeno il 50% dell'apporto totale di Azoto dovrebbe essere sotto forma di Azoto nitrico (N-NO3-).

L'elemento nutritivo più presente all'interno della pianta di pomodoro in sviluppo e del frutto è di gran lunga il Potassio, seguito dall'Azoto (N) e dal Calcio (Ca). (Figure 7 e 8)

Figura 7: Composizione in elementi di una pianta di Pomodoro

(Atherton and Rudich, 1986)

Figura 8: Composizione in elementi di un frutto di Pomodoro

(Atherton and Rudich, 1986)

2. Manuale di coltivazione del pomodoro: Principali funzioni degli elementi nutritivi

Tabella 5: Sommario delle principali funzioni degli elementi nutritivi

Nutriente | Funzione |

|---|---|

Azoto (N) | Sintesi delle proteine (crescita e resa). |

Fosforo (P) | Divisione cellulare e formazione ATP (substrato energetico delle colture). |

Potassio (K) | Trasporto degli zuccheri, apertura/chiusura stomi (osmoregolatore), cofattore molti enzimi, riduce la suscettibilità alle alte e basse temperature e agli stress in generale. |

Calcio (Ca) | Componente prevalente della parete cellulare, riduce la suscettibilità a stress (a)biotici. |

Zolfo (S) | Sintesi degli aminoacidi essenziali metionina e cistina. |

Magnesio (Mg) | Parte centrale della molecola della clorofilla. |

Ferro (Fe) | Sintesi della clorofilla. |

Manganese (Mn) | Necessario al processo di Fotosintesi, attività antiossidante. |

Boro (B) | Formazione della parete cellulare. Germinazione e allungamento del tubetto pollinico. Partecipa al metabolismo ed al trasporto degli zuccheri. |

Zinco (Zn) | Sintesi auxine (ormone). |

Rame (Cu) | Influenza il metabolismo dell'Azoto e dei carboidrati. |

Molibdeno (Mo) | Componente della nitrato reduttasi (enzima che porta da Nitrato ad Azoto Organico delle piante) e della Nitrogenasi (enzima responsabile della sintesi azotata). |

Azoto (N)

La forma azotata impiegata è un fattore fondamentale per la buona riuscita di una coltivazione di pomodoro. Il rapporto ottimale tra ammonio e nitrato dipende dalla fase fenologica e dal pH del substrato/ terreno di crescita. Le piante coltivate in un substrato solamente con azoto ammoniacale mostrano un minor peso fresco ed una maggiore suscettibilità agli stress rispetto a piante coltivate su substrato nutrito solo con azoto nitrico. L'aumento del rapporto Ammonio/ Nitrato aumenta l'EC (conducibilità elettrica) e conseguentemente riduce la resa: tuttavia raddoppiando la dose di Multi-K®, il potassio nitrato Haifa, nonostante l'incremento dell'EC è stato possibile incrementare la resa (Tabella 6).

Table 6: Effetto della forma azotata (NO3- and NH4+) sulla resa del pomodoro - esempio del vantaggio produttivo nell'impiego dell'azoto nitrico sull'azoto ammoniacale. (source: U. Kafkafi et al. 1971)

NO3- : NH4+ Ratio | N (g/pianta) | EC (dS/m) | Resa (kg/pianta) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Multi-K® Nitrato di Potassio | Haifa NIT GG Nitrato Ammonico | |||

100 : - | 6.3 | - | 1.7 | 2.5 |

70 : 30 | 6.3 | 4.4 | 2.4 | 1.98 |

63 : 37 | 6.3 | 8.7 | 2.9 | 1.20 |

59 : 41 | 6.3 | 13.2 | 3.5 | 1.00 |

100 : - | 12.6 | - | 3.1 | 3.43 |

Potassio (K)

In quanto catione principale (K+), il Potassio, bilancia le cariche negative degli acini organici e degli anioni minerali. Pertanto, un'elevata concentrazione di Potassio all'interno delle cellule è richiesta per far fronte a questo fabbisogno.

1. Bilanciamento delle cariche negative all'interno della pianta

La principale funzione del Potassio è quella di attivatore di più di 60 enzimi coinvolti nella sintesi di proteine, zuccheri, amido ecc..

Un'altra funzione è quella di tampone sul pH interno delle cellule (7-8), passando attraverso le membrane, bilanciando i protoni durante il processo fotosintetico.

Un'altra funzione è quella di tampone sul pH interno delle cellule (7-8), passando attraverso le membrane, bilanciando i protoni durante il processo fotosintetico.

2. Regolatore processi metabolici intracellulari

Regola il turgore cellulare agendo sulle cellule di guardia degli stomi.

Nel floema il Potassio contribuisce alla pressione osmotica e al trasporto metabolico delle sostanze dai "source" ai "sink" (dalle foglie ai frutti e dagli organi perenni alle radici). Attraverso quest'azione il Potassio contribuisce ad incrementare la sostanza secca ed il contenuto di zuccheri dei frutti ma anche il turgore dei frutti e conseguentemente la loro shelf-life.

In aggiunta il Potassio ha importanti ruoli fisiologici:

3. Regolazione della pressione osmotica

- Migliora la resistenza all'appassimento.(Bewley and White ,1926, Adams et al ,1978)

- Migliora la resistenza natura della pianta agli stress biotici. (Potassium and Plant Health, Perrenoud, 1990).

- Riduce l'insorgenza di rotture di colore e "ciccato". (Winsor and Long, 1968)

- Incrementa i solidi solubili all'interno dei frutti. (Shafik and Winsor,1964)

- Migliora il sapore dei frutti. (Davis and Winsor, 1967)

Figura 9: Effetto della dose di K sulla resa e la qualità del pomodoro da industria

Il Licopena è un importante pigmento presente all'interno dei pomodori, un potentissimo antiossidante fondamentale per la salute umana.

Aumentando la dose d'impiego di Multi-K® è stato possibile incrementare la concentrazione di questo pigmento nei frutti.

La relazione tra Potassio e Licopene è spiegata dalla curva di dose ottimale (Fig. 10).

La relazione tra Potassio e Licopene è spiegata dalla curva di dose ottimale (Fig. 10).

♦ Clicca per scoprire i Multi-vantaggi del Nitrato Potassico Haifa ♦ |

Figure 10: The effect of Multi-K® rate on lycopene yield in processing tomatoes

Lycopene yield (mg / plant) |  |

|---|---|

K rate(g/plant) |

Multi-K® was applied, as a source of potassium, either by itself or blended with other N and P fertilizers, to processing tomatoes. The different application methods, side-dressing dry fertilizers or combined with fertigation, were compared in a field trial (Table 7). Multi-K® increased the yield (dry matter) and the brix level as can be seen in Figure 11.

Multi-K® was applied, as a source of potassium, either by itself or blended with other N and P fertilizers, to processing tomatoes. The different application methods, side-dressing dry fertilizers or combined with fertigation, were compared in a field trial (Table 7). Multi-K® increased the yield (dry matter) and the brix level as can be seen in Figure 11.Table 7: Layout of a field trial comparing different Multi-K® application methods and rates, as a source of K, combined with other N and P fertilizers:

Method of application | N-P2O5-K20 kg/ha | |

|---|---|---|

Base-dressing and side-dressing | 120-140-260 | 1) 10 days prior to transplanting: 65% of N & K rates, and the entire P |

2) 26 days after transplanting (initial flowering): 10% of N & K rates | ||

3) 51 days after transplanting (initial fruit-set ): 25% of N & K rates as Multi-K® | ||

Base-dressing and Fertigation I | 120-140-260 | 10 days prior to transplanting: 30% of N, P & K rates, 350 kg/ha of Multi-K® in a blend: 12-20-27. |

During the entire plant development stages, 70% of N-P-K as Multi-K® + Soluble NPK’s + Multi-P (phos. acid), 12 weekly applications by fertigation | ||

Base-dressing and Fertigation II | 160-180-360 (34% higher rate) | 10 days prior to transplanting: 30% of N, P & K rates as 400 kg/ha, a Multi-K® in a blend: 12-20-27. |

During the entire plant development stages, 70% of N-P-K as Multi-K® + Soluble NPK’s + Multi-P (phos. acid), 12 weekly applications by fertigation |

Figure 11: The effect of application method and rates of Multi-K® potassium nitrate on the dry matter yield and brix level of processing tomatoes cv Peto.

Dry matter yield (ton/ha) |  |

Calcium (Ca)

Calcium is an essential ingredient of cell walls and plant structure. It is the key element responsible for the firmness of tomato fruits. It delays senescence in leaves, thereby prolonging leaf's productive life, and total amount of assimilates produced by the plans.

Temporary calcium deficiency is likely to occur in fruits and especially at periods of high growth rate, leading to the necrosis of the apical end of the fruits and a development of BER syndrome.

3. Tomato crop guide: Nutrients deficiency symptoms

Nitrogen

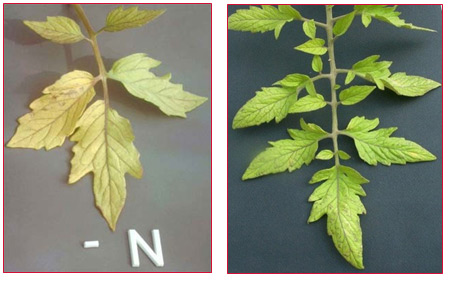

The chlorosis symptoms shown by the leaves on Figure 12 are the direct result of nitrogen deficiency. A light red cast can also be seen on the veins and petioles. Under nitrogen deficiency, the older mature leaves gradually change from their normal characteristic green appearance to a much paler green. As the deficiency progresses these older leaves become uniformly yellow (chlorotic). Leaves become yellowish-white under extreme deficiency. The young leaves at the top of the plant maintain a green but paler color and tend to become smaller in size. Branching is reduced in nitrogen deficient plants resulting in short, spindly plants. The yellowing in nitrogen deficiency is uniform over the entire leaf including the veins. As the deficiency progresses, the older leaves also show more of a tendency to wilt under mild water stress and senesce much earlier than usual. Recovery of deficient plants to applied nitrogen is immediate (days) and spectacular.

Figure 12: Characteristic nitrogen (N) deficiency symptom

Haifa's solution: Multi-K™ potassium nitrate fertilizer

Phosphorus

The necrotic spots on the leaves on Fig. 13 are a typical symptom of phosphorus (P) deficiency. As a rule, P deficiency symptoms are not very distinct and thus difficult to identify. A major visual symptom is that the plants are dwarfed or stunted. Phosphorus deficient plants develop very slowly in relation to other plants growing under similar environmental conditions but with ample phosphorus supply.

Phosphorus deficient plants are often mistaken for unstressed but much younger plants.

Developing a distinct purpling of the stem, petiole and the lower sides of the leaves. Under severe deficiency conditions there is also a tendency for leaves to develop a blue-gray luster. In older leaves under very severe deficiency conditions a brown netted veining of the leaves may develop.

Figure 13: Characteristic phosphorus (P) deficiency symptom

Haifa's solution: Haifa MAP™ (Mono Ammonium Phosphate) and Haifa MKP™ (Mono Potassium Phosphate)

Potassium

The leaves on the right-hand photo show marginal necrosis (tip burn). The leaves on the left-hand photo show more advanced deficiency status, with necrosis in the interveinal spaces between the main veins along with interveinal chlorosis. This group of symptoms is very characteristic of K deficiency symptoms.

Figure 14: Characteristic potassium (K) deficiency symptoms.

The onset of potassium deficiency is generally characterized by a marginal chlorosis, progressing into a dry leathery tan scorch on recently matured leaves. This is followed by increasing interveinal scorching and/or necrosis progressing from the leaf edge to the midrib as the stress increases. As the deficiency progresses, most of the interveinal area becomes necrotic, the veins remain green and the leaves tend to curl and crinkle. In contrast to nitrogen deficiency, chlorosis is irreversible in potassium deficiency. Because potassium is very mobile within the plant, symptoms only develop on young leaves in the case of extreme deficiency.

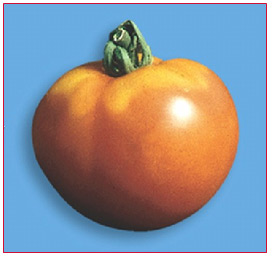

Typical potassium (K) deficiency of fruit is characterized by color development disorders, including greenback, blotch ripening and boxy fruit (Fig. 15).

Figure 15: Characteristic potassium (K) deficiency symptoms on the fruit

Haifa's solution: Multi-K™ potassium nitrate fertilizer

Calcium

These calcium-deficient leaves (Fig. 16) show necrosis around the base of the leaves. The very low mobility of calcium is a major factor determining the expression of calcium deficiency symptoms in plants. Classic symptoms of calcium deficiency include blossom-end rot (BER) burning of the end part of tomato fruits (Fig. 17). The blossom-end area darkens and flattens out, then appearing leathery and dark brown, and finally it collapses and secondary pathogens take over the fruit.

Figure 16: Characteristic calcium (Ca) deficiency symptoms on leaves

Figure 17: Characteristic calcium (Ca) deficiency symptoms on the fruit

All these symptoms show soft dead necrotic tissue at rapidly growing areas, which is generally related to poor translocation of calcium to the tissue rather than a low external supply of calcium. Plants under chronic calcium deficiency have a much greater tendency to wilt than non-stressed plants.

Haifa's solution: Haifa Cal™ - Calcium nitrate fertilizer

Magnesium

Magnesium-deficient tomato leaves (Fig. 18) show advanced interveinal chlorosis, with necrosis developing in the highly chlorotic tissue. In its advanced form, magnesium deficiency may superficially resemble potassium deficiency. In the case of magnesium deficiency the symptoms generally start with mottled chlorotic areas developing in the interveinal tissue. The interveinal laminae tissue tends to expand proportionately more than the other leaf tissues, producing a raised puckered surface, with the top of the puckers progressively going from chlorotic to necrotic tissue.

Figure 18: Characteristic magnesium (Mg) deficiency

Haifa's solution: Magnisal - Magnesium nitrate fertilizer

Sulfur

This leaf (Fig. 19) shows a general overall chlorosis while still retaining some green color. The veins and petioles exhibit a very distinct reddish color. The visual symptoms of sulfur deficiency are very similar to the chlorosis found in nitrogen deficiency. However, in sulfur deficiency the yellowing is much more uniform over the entire plant including young leaves. The reddish color often found on the underside of the leaves and the petioles has a more pinkish tone and is much less vivid than that found in nitrogen deficiency. With advanced sulfur deficiency brown lesions and/or necrotic spots often develop along the petiole, and the leaves tend to become more erect and often twisted and brittle.

Figure 19: Characteristic sulfur (S) deficiency

Manganese

These leaves (Fig. 20) show a light interveinal chlorosis developed under a limited supply of Mn. The early stages of the chlorosis induced by manganese deficiency are somewhat similar to iron deficiency. They begin with a light chlorosis of the young leaves and netted veins of the mature leaves especially when they are viewed through transmitted light. As the stress increases, the leaves take on a gray metallic sheen and develop dark freckled and necrotic areas along the veins. A purplish luster may also develop on the upper surface of the leaves.

Figure 20: Characteristic manganese (Mn) deficiency

Haifa's solution: Haifa Micro™

Molybdenum

These leaves (Fig. 21) show some mottled spotting along with some interveinal chlorosis. An early symptom for molybdenum deficiency is a general overall chlorosis, similar to the symptom for nitrogen deficiency but generally without the reddish coloration on the undersides of the leaves. This results from the requirement for molybdenum in the reduction of nitrate, which needs to be reduced prior to its assimilation by the plant. Thus, the initial symptoms of molybdenum deficiency are in fact those of nitrogen deficiency. However, molybdenum has also other metabolic functions within the plant, and hence there are deficiency symptoms even when reduced nitrogen is available. At high concentrations, molybdenum has a very distinctive toxicity symptom in that the leaves turn a very brilliant orange.

Figure 21: Characteristic molybdenum (Mo) deficiency

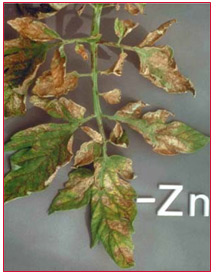

Zinc

This leaf (Fig. 22) shows an advanced case of interveinal necrosis. In the early stages of zinc deficiency the younger leaves become yellow and pitting develops in the interveinal upper surfaces of the mature leaves. As the deficiency progresses these symptoms develop into an intense interveinal necrosis but the main veins remain green, as in the symptoms of recovering iron deficiency.

Figure 22: Characteristic zinc (Zn) deficiency symptoms.

Haifa's solution: Haifa Micro™

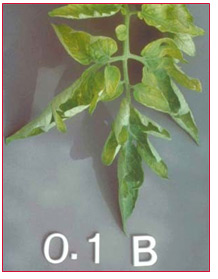

Boron

This boron-deficient leaf (Fig. 23) shows a light general chlorosis. Boron is an essential plant nutrient, however, when exceeding the required level, it may be toxic. Boron is poorly transported in the phloem. Boron deficiency symptoms generally appear in younger plants at the propagation stage. Slight interveinal chlorosis in older leaves followed by yellow to orange tinting in middle and older leaves. Leaves and stems are brittle and corky, split and swollen miss-shaped fruit (Fig. 24).

Figure 23: Characteristic boron (B) deficiency symptoms on leaves

Figure 24: Characteristic boron (B) deficiency symptoms on fruits

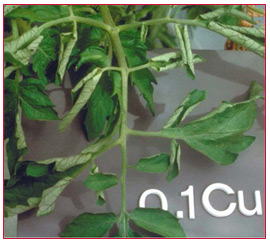

Copper

These copper-deficient leaves (Fig. 25) are curled, and their petioles bend downward. Copper deficiency may be expressed as a light overall chlorosis along with the permanent loss of turgor in the young leaves. Recently matured leaves show netted, green veining with areas bleached to a whitish gray. Some leaves develop sunken necrotic spots and have a tendency to bend downward.

Figure 25: Characteristic copper (Cu) deficiency symptoms.

Haifa's solution: Haifa Micro™

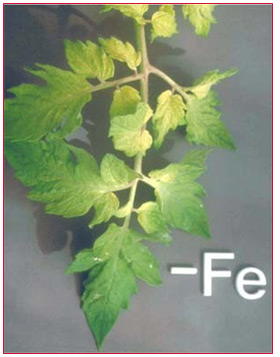

Iron

These iron-deficient leaves (Fig. 26) show intense chlorosis at the base of the leaves with some green netting. The most common symptom for iron deficiency starts out as an interveinal chlorosis of the youngest leaves, evolves into an overall chlorosis, and ends as a totally bleached leaf. The bleached areas often develop necrotic spots. Up until the time the leaves become almost completely white they will recover upon application of iron. In the recovery phase the veins are the first to recover as indicated by their bright green color.

This distinct venial re-greening observed during iron recovery is probably the most recognizable symptom in all of classical plant nutrition. Because iron has a low mobility, iron deficiency symptoms appear first on the youngest leaves. Iron deficiency is strongly associated with calcareous soils and anaerobic conditions, and it is often induced by an excess of heavy metals.

Figure 26: Characteristic iron (Fe) deficiency symptoms

Haifa's solution: Haifa Micro™

4. Tomato crop guide: Leaf analysis standards

In order to verify the correct mineral nutrition during crop development, leaf samples should be taken at regular intervals, beginning when the 3rd cluster flowers begin to set. Sample the whole leaf with petiole, choosing the newest fully expanded leaf below the last open flower cluster. Sufficiency leaf analysis ranges for newest fully-expanded, dried whole leaves are:

Table 8: Nutrients contents in tomato plant leaves

A. Macro and secondary nutrients

Nutrient | Conc. in leaves (%) | |

|---|---|---|

Before fruiting | During fruiting | |

N | 4.0-5.0 | 3.5-4.0 |

P | 0.5-0.8 | 0.4-0.6 |

K | 3.5-4.5 | 2.8-4.0 |

Ca | 0.9-1.8 | 1.0-2.0 |

Mg | 0.5-0.8 | 0.4-1.0 |

S | 0.4-0.8 | 0.4-0.8 |

B. Micronutrients

Nutrient | Conc. in leaves (ppm) | |

|---|---|---|

Before fruiting | During fruiting | |

Fe | 50-200 | 50-200 |

Zn | 25-60 | 25-60 |

Mn | 50-125 | 50-125 |

Cu | 8-20 | 8-20 |

B | 35-60 | 35-60 |

Mo | 1-5 | 1-5 |

Toxic levels for B, Mn, and Zn are reported as 150, 500, and 300 ppm, respectively

Table 9: Overall requirements of macro-nutrients under various growth conditions

Fertilizer | Yield (ton/ha) | N | P2O5 | K2O | CaO | MgO |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Outdoor | 80 | 241 | 62 | 416 | 234 | 67 |

150 | 417 | 108 | 724 | 374 | 110 | |

Processing | 60 | 196 | 50 | 336 | 203 | 56 |

100 | 303 | 78 | 522 | 295 | 84 | |

Tunnels | 100 | 294 | 76 | 508 | 279 | 80 |

200 | 536 | 139 | 934 | 463 | 138 | |

Greenhouse | 120 | 328 | 85 | 570 | 289 | 86 |

240 | 608 | 158 | 1065 | 491 | 152 |

Need more information about growing tomato? You can always return to the tomato fertilizer & tomato crop guide table of contents or the tomato plant stages

For more information visit our iron deficiency in plants and soils!